Picture the scene. It’s 2017. My dad and I have just watched a nostalgia-packed weekend of racing at Knockhill’s Super Touring Festival, where cars from the world’s most competitive Super Touring series re-lived their ‘90s glory years on-track.

We wandered the paddock afterwards, watching the teams pack up their awnings, admiring the bespoke racing machines that captured the imaginations of hundreds of thousands of fans in their heyday.

Manufacturers like Audi, Ford, Honda, Nissan, Peugeot, Renault, Vauxhall and Volvo spent millions of pounds developing their contenders. Even Formula 1 drivers and teams were attracted to the cut and thrust of the increasingly popular championship and its burgeoning commercial opportunities.

Silverstone, England. 4th October 1992. John Cleland, Vauxhall Cavalier GSi, retired, collides with Steve Soper, BMW 318i, retired. Photographer: LAT Photographic, Motorsport Images

Outfits like Williams, Prodrive and TWR built and engineered Super Tourers, with foreign talents such as Frank Biela, Tom Kristensen, Johnny Cecotto and Gabriele Tarquini joining the British ‘2 litre Touring Car Formula’ between 1990 and 2000.

But British drivers more than held their own against the influx of international superstars. Home-grown heroes like James Thompson, Jason Plato and Will Hoy faced off against the incomers with crowds in their thousands flocking trackside to watch all the paint-swapping action.

However, one driver probably did more for the popularity of the BTCC than any other – John Cleland.

“I’m going for first”

The two-time BTCC champion was pure touring car box office. His frequent quips, emotive in-car displays (“I’m going for first!”) and race craft were catnip for TV producers, showcased by quality BBC coverage and its enthusiastic Murray Walker-led commentary.

In the 1992 BTCC finale, Cleland and Tim Harvey went head-to-head for the title, only for Harvey’s teammate Steve Soper to cynically punt Cleland’s Vauxhall Cavalier out of the race in spectacular fashion. The race and its subsequent fallout made national news headlines, securing touring cars’ popularity with the general public. Touring Car racing was no longer just the preserve of hardcore racing fans.

It seems absurd, therefore, that it took another five years for an official BTCC videogame to hit the shelves. Yet TOCA Touring Car Championship for the original Sony PlayStation arrived in November 1997. And it was worth the wait.

As someone who continuously watched and memorised the BTCC’s season review VHS tapes, I had never been as excited about a videogame before. To think it came out 25 years ago makes me feel old, very old.

TOCA’s miracle

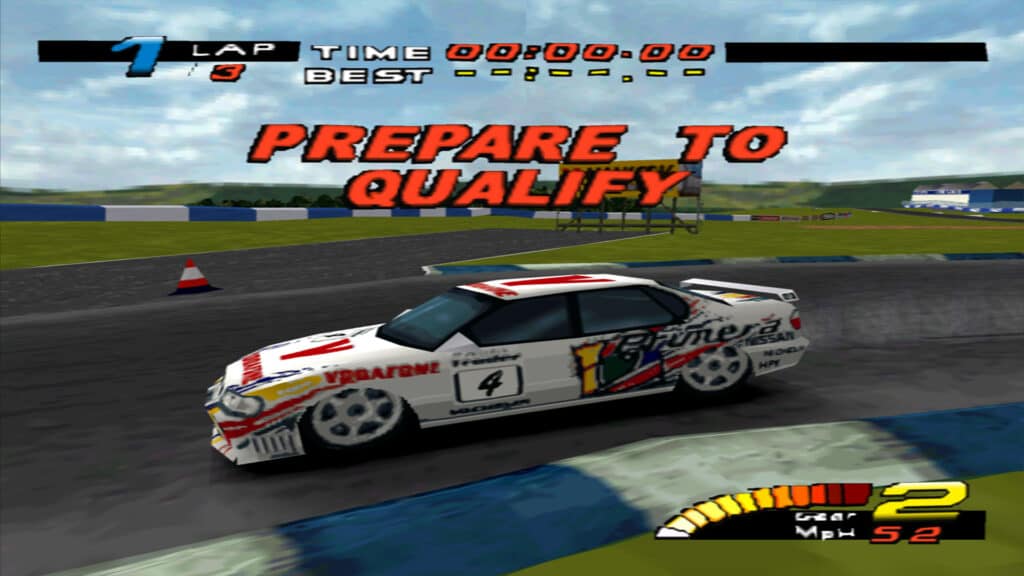

Developed and published by Codemasters, the game featured the officially licenced 1997 BTCC season. Routinely known simply as ‘TOCA’ – in reference to the organisation and administration body for the championship – the game was a hit with fans of the series.

But TOCA’s fun handling model and graphics gave the series a whole new (and younger) audience. Part of the appeal of Super Touring racing was the cars themselves. They looked like the standard family saloons its audience drove to the supermarket every weekend (with a wing and splitter, of course).

For example, my dad owned a Vauxhall Cavalier GSi 2000, which was the marque’s model of choice to launch its assault on the 2-litre Touring Car Formula in 1990. The everyman appeal of the series extended to 1997 too, when kids (and their parents) enjoyed thrashing souped-up versions of their own Lagunas, A4s and Primeras around authentically reproduced British circuits, including Oulton Park, Brands Hatch and Silverstone.

The tracks were constructed using Ordnance Survey data. Although no match for modern-day laser-scanning techniques, tracks were accurately reproduced and featured convincing elevation changes. Unfortunately, I was always bothered by Knockhill’s skybox and elevation changes, as it gave the circuit some additional hills and a rather flat run through Duffus Dip.

Still, I was fortunate to have a digital re-creation of my home track at all, given many of the BTCC tracks had never appeared in a videogame before. As a result, Thruxton, Croft and Knockhill all made their first notable videogame appearances in TOCA.

We have lift-off (oversteer)

Occasional BTCC driver and Top Gear presenter Tiff Needell even made an appearance, using his authoritative voice to introduce each round in the career mode. TOCA captured the essence of the BTCC perfectly. Not only were all the vehicles, tracks and drivers faithfully reproduced, but the cars felt like touring cars.

Occasionally cited as a bugbear of the game, TOCA’s cars handled like caffeine-infused shopping trollies. Twitchy was an understatement. Carry too much speed into a corner and you’d quickly find yourself upside down in a mess of Patrick Watts’ Peugeot parts.

However, a cursory glance at real onboard videos from the era shows the cars were a handful at the best of times; teams set them up to be as nervous as possible to extend the front axle’s tyre life over a race distance. The physics were on the realistic side of fun.

The hustle and bustle of touring car racing was captured perfectly too, with multi-car incidents occurring organically. It was also possible to strategically remove your opponents from a race (or ‘Sopering’ as I used to call it). This worked extremely well in the wet at Thruxton, where a slight nudge going into the final chicane could invert your opponent into a DNF (former BTCC commentator Charlie Cox had some experience of this too, see video above).

Atmospheric details – from in-car cameras to the sound made over gravel, grass and kerbs – made the game almost sim-like in its approach. Transmission whine and an in-car camera also emphasised Codemasters’ attention to detail.

But TOCA had its downsides…

The downsides

Like any game, TOCA isn’t perfect. The career mode, which takes players through the genuine 1997 BTCC season, was more arcade than sim. Sure, the races felt realistic, but Codemasters forced players to attain a certain number of points per round in order to progress.

It was doubly annoying as rounds three and four from Silverstone featured two wet races, where TOCA’s twitchy handling was exacerbated by the slick conditions. Progress was therefore difficult unless you had racked up big points in the first two races at Donington. (Oddly enough, in the real-world 1997 championship, rounds three and four were entirely dry!)

The game ran at a steady 24 frames per second but suffered from frequent pop-in and muddy textures. Gran Turismo launched just one month later and featured stupendous graphics – TOCA suddenly looked a little shabby in comparison.

Two’s company, three’s impossible

Although TOCA had a two-player split-screen mode, AI cars were sadly absent, taking away the game’s manic racing focus (the PC version could support up to eight players via LAN, however).

More disappointing was the lack of practice sessions in career mode. Players were thrown in at the deep end with just three laps to learn the track and set a qualifying time. As well as that, the AI were often much too quick in qualifying trim. In fact, apart from the main Championship, the only other game modes to keep players occupied were Time Trial, Single Race and Two Player races. Not much, then.

You also couldn’t set-up your car between sessions, which is odd given how well other aspects of the BTCC have been simulated. Private entrants like Lee Brookes, Colin Gallie and three-time BTCC champion Matt Neal were also notable by their absence, licencing red tape perhaps blocking their appearance in-game.

As a result, TOCA sat in the middle ground between simulation and arcade, not quite fully achieving either. But the game was still fun. A lot of fun.

Cheat mode enabled

Despite the game leaning towards the simulation side of racing, Codemasters still injected a little incongruity into proceedings. Players could unlock numerous cheats, including the addition of a Pink Cadillac and rocket-powered Tank – ideal if you’ve ever fantasised about firing a heavy-calibre weapon at Tim Harvey’s Peugeot (which I often did).

A new track was also available. The figure-8 Lavaland circuit could be unlocked by completing the game or by typing in the cheat code ‘JHAMMO’. (Every correctly input cheat code would be accompanied by Needell’s dulcet tones confirming: “cheat mode enabled”. Bliss.)

Lavaland featured heavily graded roads with a rollercoaster-like surface completely unsuitable for touring car racing. It was like travelling through an underworld version of Kielder Forest. I didn’t bat an eyelid at these frankly bizarre additions to TOCA when I was a teenager, but their addition makes zero sense looking back now.

Anything for you, John

The everyman appeal of the BTCC translated to healthy sales for TOCA, with the game shifting around 600,000 copies in six months, earning over €21million according to figures reported by Gamespot. Not bad for a niche, PlayStation-only title. Although a PC version followed in 1998, with a bizarre yet passable Game Boy Colour edition released in 2000.

Like many, I fondly remember TOCA’s re-creation of the spectacular world of the BTCC. For me, it was the first officially licenced console racing game that produced a convincing take on its source material. Well, with the possible exception of Psygnosis/Bizarre Creations’ F1 series, but I was a BTCC fanboy.

Realistic graphics, sounds, handling and circuits combined to produce an authentically pure BTCC experience that’s arguably never been toppled. Motorsport Games’ forthcoming BTCC game certainly has a lot to live up to. But hopes are high given the quality of rFactor 2’s recent BTCC content.

Dad and I are back at Knockhill in 2017, watching John Cleland pack away his self-funded team’s equipment. His ‘97 Vectra – the same one as depicted in TOCA* – is sitting clear of its transporter, ready to be loaded. “Can you guys give us a push?” he asked, looking exactly the same as he did 20 years before.

“Anything for you, John”, replied my starstruck father.

Clearly, my dad still has a deep – and in this case, embarrassing – connection with the glory days of the BTCC. I do too, and Codemasters’ wonderful work on TOCA Touring Car Championship is a large part of that nostalgia.

With much less cringe.

*John Cleland owns a 1997 Vauxhall Vectra that has the 1998 aero package and livery. Thankfully, the ‘98 car was a huge improvement with Cleland taking two wins – including the lauded ‘Mansell race’, thought to be one of the greatest touring car races of all time.

Chat with the Community

Sign Up To CommentIt's completely Free