We’ve been lucky enough to have several great new rally games recently, not least art of rally and Rush Rally Origins. But with them comes a trend: Both of these games eschew traditional helmet cam and low ‘chase cam’ viewpoints, instead offering elevated ‘top-down’ cameras, deliberately detaching the player from the action.

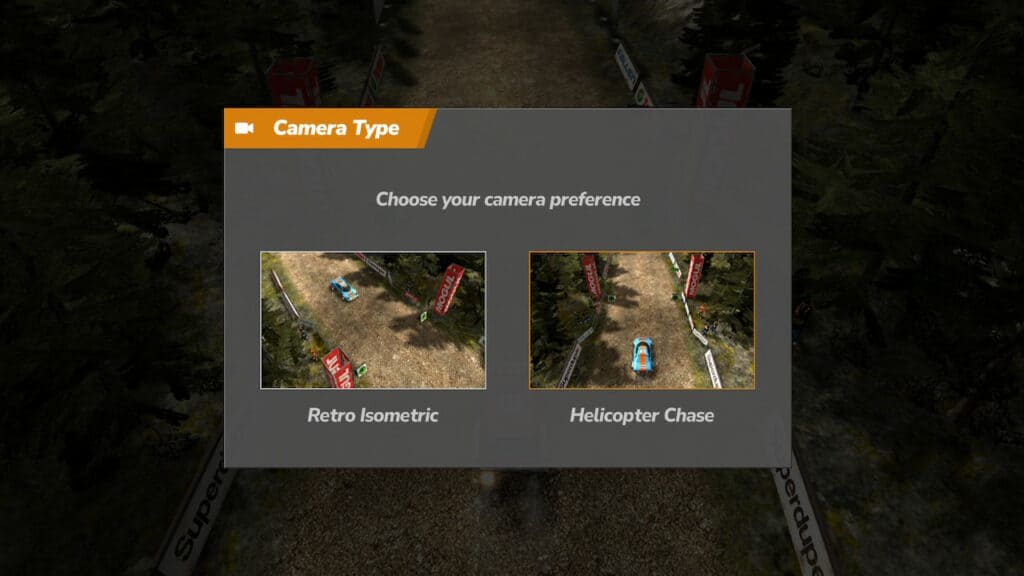

You can’t feel the slide of your car under you like you can in cockpit cam; you have to see its external motion and gauge that instead, which is a fundamentally different experience. But with more top-down games like Rally Cross Challenge (RXC) on the horizon and the recent Super Woden GP again borrowing from that isometric perspective, why is this restricted, retro-tastic camera placement so popular in new racing games? Let’s find out.

In gaming, a true isometric viewpoint gives you a 2D view of a 3D world and was particularly popular in the arcades in the late 1980s and on home consoles in the 1990s at the respective times when neither platform could provide true 3D visuals convincingly.

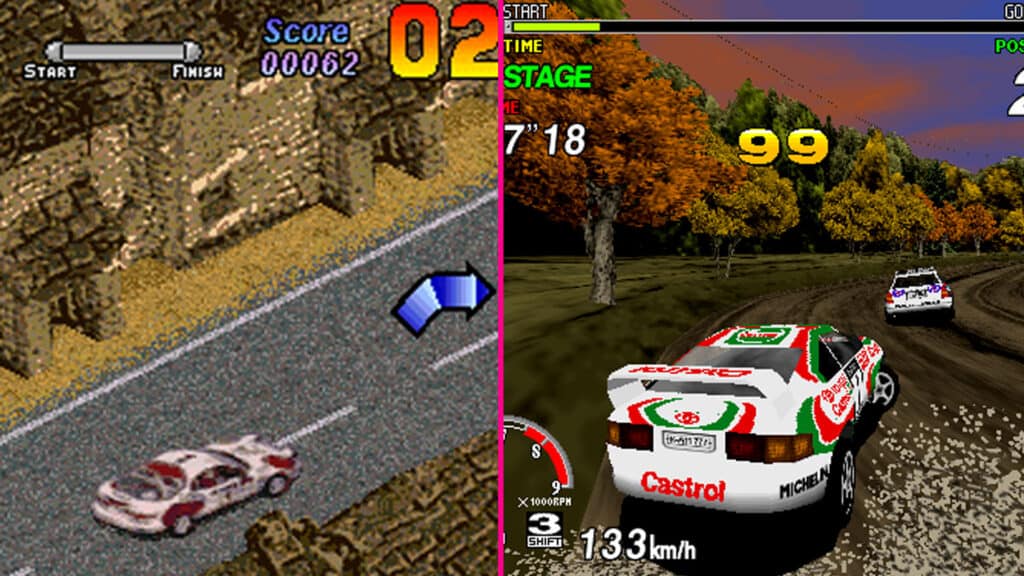

Drawing a 3D environment in 2D from an elevated angle meant that games could still look more realistic without calculating floating points and 3D texture mapping. As a result, FIFA International Soccer looked like Match of the Day, and Super Off-Road looked like you were sitting way up in the grandstands at a truck fest. But even back then, there’s no way anyone would choose to play an isometric arcade racer like Gaelco’s World Rally Championship (1993) when the glorious 3D of Sega Rally Championship (1995) was standing right next to it.

Isometric angles just weren’t as sexy as full 3D.

What irony, then, that polygonal 3D is now emulating isometric 3D when it used to be the other way round out of necessity.

The reason for early polygonal isometric-styled games was probably a technical one. While it’s hard to believe now, back in the early-1990s, it was a dream to have a true 3D Micro Machines game. One where you raced your tiny car through the hazards of a breakfast table with cereal boxes and maple syrup bottles towering above you.

Sadly, even the then-cutting edge technical behemoth of the original Sony PlayStation couldn’t manage that. Why? Well, once you’ve drawn the competitors’ cars, the tablecloth, the bowls and spoons and cereal boxes, you’ve used up all your calculations but still need to draw what’s beyond the table. Kitchens are cluttered places, so it just wasn’t feasible to render them in full 3D until the next generation and Dreamcast’s Toy Commander.

No, it made more sense to restrict what the camera could see, and pack the most detail possible into that confined frame, and that’s what we got with Micro Machines V3.

Fast-forward a couple of decades and that’s actually likely to be the reason why Rush Rally Origins looks so good on low-powered hardware like phones and tablets. The tilted camera view doesn’t show you the horizon, and as you tip the camera down, there’s an exponential drop in the number of trees you need to draw. These remaining trees can then cast dynamic shadows without having said shadows pop-in in the middle distance, and the game can run at 60fps even at full detail levels on Nintendo Switch.

art of rally’s camera isn’t fixed, instead turning with your car so that you always see in front of you (which is the same as the original Rush Rally’s viewpoint, which is also selectable in Origins). That downwards tilt is pronounced, but still often lets you see into the distance, for which it pays the price in terms of processor load, especially on Switch. Let’s ask a bold question, then: might a true isometric angle have worked better in art of rally?

I would argue it would, especially since art of rally’s predecessor Absolute Drift is by far the more convincing Switch conversion, and – lo and behold – uses a fixed, isometric style camera angle which works really well for its more rally-esque challenges.

With so many approaches to the top-down racer, can we say which is best? Well, the elevated chase cam is the easiest to control, just as it was way back in the original Virtua Racing. While far from 1:1 movement of both camera and car in art of rally, you do get a good feel for the inertia of your vehicle. It’s easier to get the hang of this viewpoint compared to the ‘radio controlled car’ approach of an isometric perspective, which can (confusingly for many) make pushing left make your car go right if you’re racing ‘down the screen’.

Then there’s isometric 2D games like the World Rally Championship arcade game, which is detailed, certainly, but is so zoomed-in to make the car the star that it just moves too fast for you to react to corners on sight, forcing you to react to prompts rather than actually drive the tracks. Not so hot.

No, what a top-down game needs is a dynamic isometric-style camera. And that’s exactly what Rush Rally Origins’ isometric viewpoint offers. The polygonal 3D allows for seamless scaling of the cars and environments, which means fast sections are zoomed out allowing you to see the corners in time to prepare for them. Conversely, as your car slows down, the camera zooms in to give you a detailed view of your vehicle power-drifting around a hairpin with mud and dust flying.

It’s truly the best of both worlds; the game is playable despite the unnatural viewpoint and it also gives you close-up splendour when you have enough time to enjoy it. Perfect.

There’s no denying there’s a stigma attached to top-down racing games by some hardcore fans, probably because such games are fundamentally unrealistic, which means you’re unavoidably playing at racing. But with the 25-year pursuit of realism sapping a lot of colour from what always used to be an exuberant and fantastical genre, it’s important we allow ourselves to enjoy simply playing a game sometimes. Long live the top-down racer.

Chat with the Community

Sign Up To CommentIt's completely Free