It’s pretty impossible for anyone under the age of 25 to understand exactly what made gaming so different in the 1980s and early 1990s compared with today.

With modern consoles like PS5 and Xbox Series X offering something close to the highest-end PC gaming available, the games we’re playing are virtually identical across the three non-Nintendo formats – just shinier and smoother on the more capable kit.

But back in those two decades it just wasn’t like that. I know I run the risk of ‘back in my day’ comments, but I’ll admit I’ll be 40 next year. At home, we didn’t just have rougher versions of arcade games. Sometimes we even had to put up with games that didn’t even have music in them.

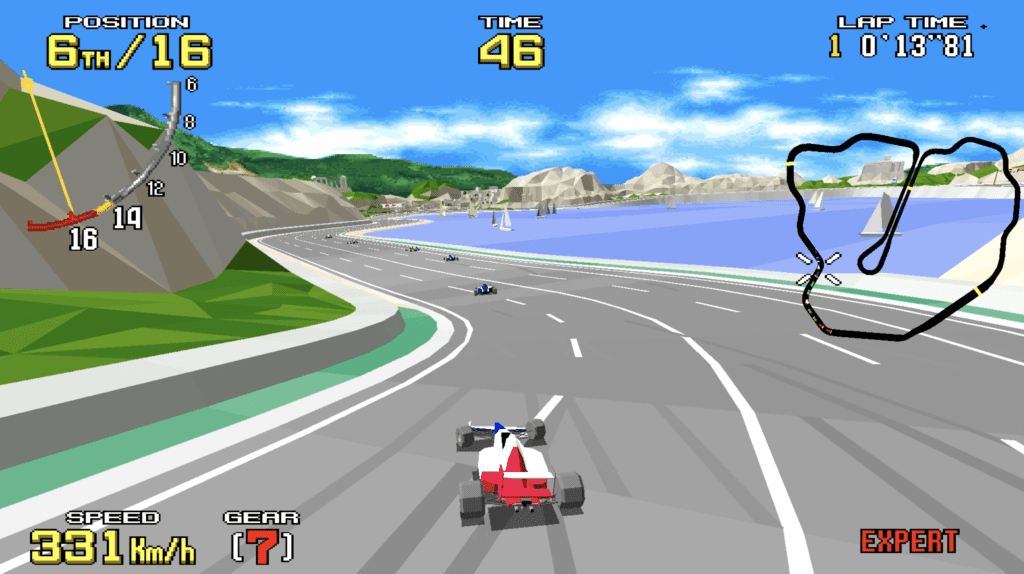

Why? Because having music to compute slowed the visuals down too much to make it playable. I’m serious, Star Wars on Spectrum actually did this. Yet we’d lap it up. We’d pay £70 (£142 in today’s money) for Virtua Racing on Mega Drive even though it ran at 15fps with a fraction of the polygons of the arcade version and the magazines still spouted hyperbole like “Virtua Racing? Virtua Sex, more like” in their previews.

The simple fact was that you just couldn’t play the most amazing games in your home, even if you were buying something with the same name. For the real thing, you had to go to the arcade. And in the arcades, Sega was king – especially when it came to racing games.

With Yu Suzuki at the development helm, Sega was clearly hell-bent on creating the perfect three-minute motorsport experience. On the screen, games swiftly moved from Hang-On’s flat-but-fast ribbon to Super Hang-On’s hills and turbo button.

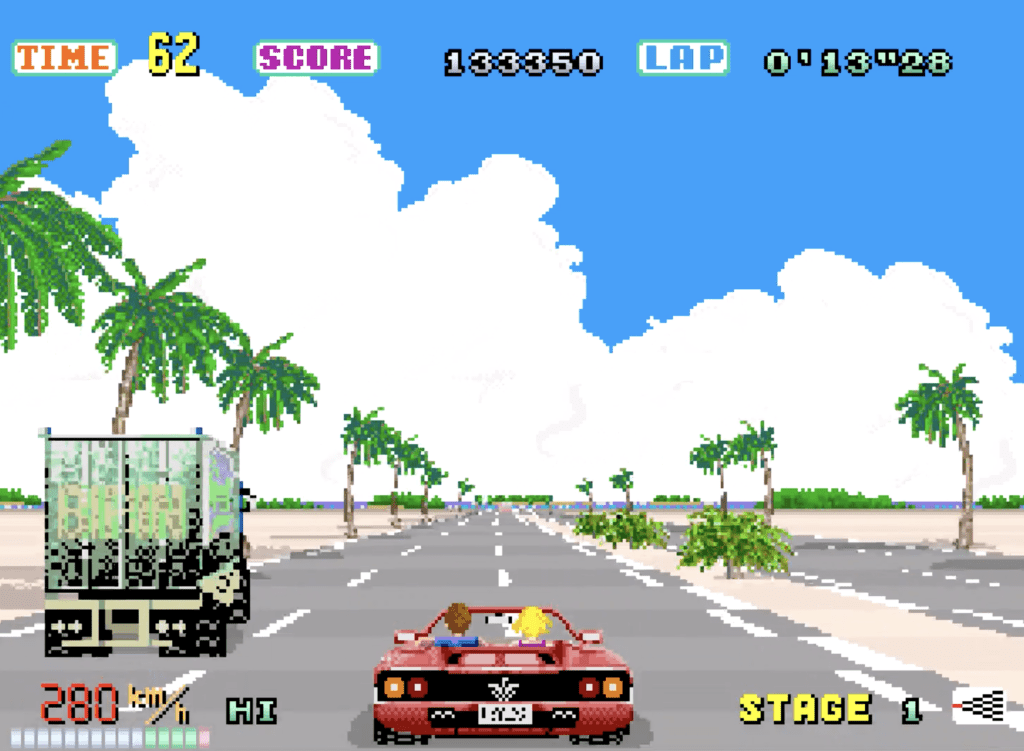

Then came OutRun’s screen-filling tunnel and Power Drift’s pseudo-3D rollercoaster-esque raceways, all made entirely of flat, scaled sprites. Off the screen, Sega’s AM4 department was manufacturing deluxe cabinets that featured motorbikes to sit on and cars to get into.

I’ll never forget playing the hydraulic OutRun cabinet at the age of 10, singing along with the music because I knew it from my loved-but-objectively-pitiful Sega Game Gear version.

Seeing such detail, such fluidity and feeling the difference in control when you played an arcade game was a revelation. Even now, in the days of force feedback Fanatec wheels, racing seats, huge TVs and infinite credits, there’s nothing quite like the old rush of playing an arcade cabinet.

And when your money was limited, every second of a credit was savoured. You’d do anything to keep the game alive and hit the next checkpoint because after that moment was over, you had to get out and go home to your ZX Spectrum version. As I said, younger gamers simply can’t imagine that gulf between what you could try and what you could keep.

But Sega knew what it was doing when it made these games special. For instance, have you ever noticed that after the first corner in OutRun, your car moves ever so slightly to the right without you pressing anything? Now, why would it do that?

Well, when you have an analogue wheel in your hand with progressive steering, you think you’ve straightened the car (and in truth, you would have done) but instead, the game makes you feel like you need to turn the wheel a little more – which you do, resulting in you moving slightly to the left instead.

Microcorrections ensue. The car feels free. By the time you reach the second turn, your brain has decided that you’re clearly driving in 3D space and also decided that the control in OutRun is amazing. Compared to the digital on/off steering of most home games at the time, it’s another level of quality. After the first stage, the game never pulls this stunt again, instead, giving you the precision you need to chase high scores. It’s genius.

And let’s take a moment to consider the competition because there were some great pretenders, but none that could topple Sega.

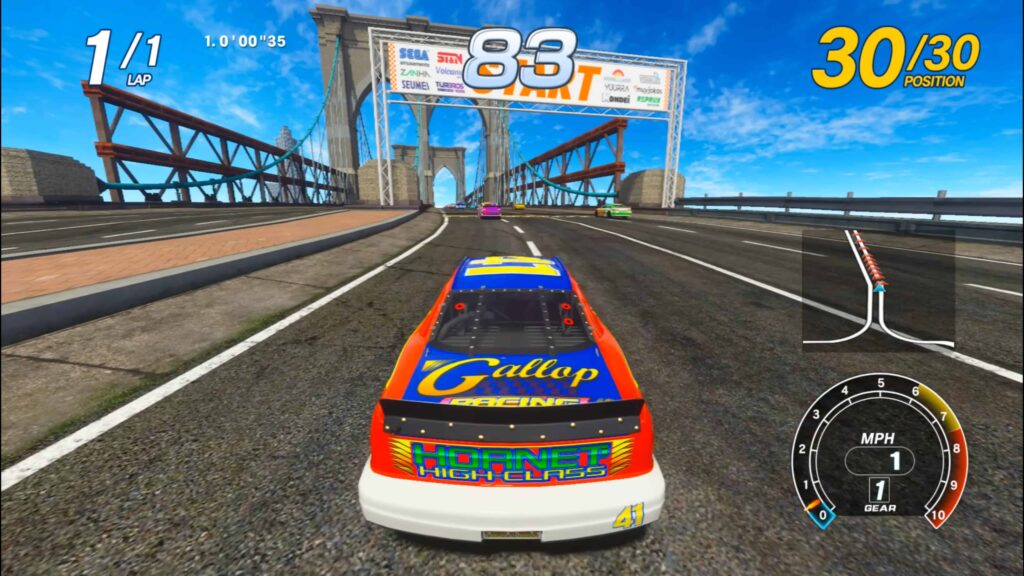

Ridge Racer has one and a bit tracks compared to Daytona USA’s three unique and varied offerings. Nintendo was nowhere, with only Cruis’n USA to offer as racing competition. Sure, you could knock over street lamps which was fun, but the frame rate and detail were nowhere near what was already happening across the floor of the arcade.

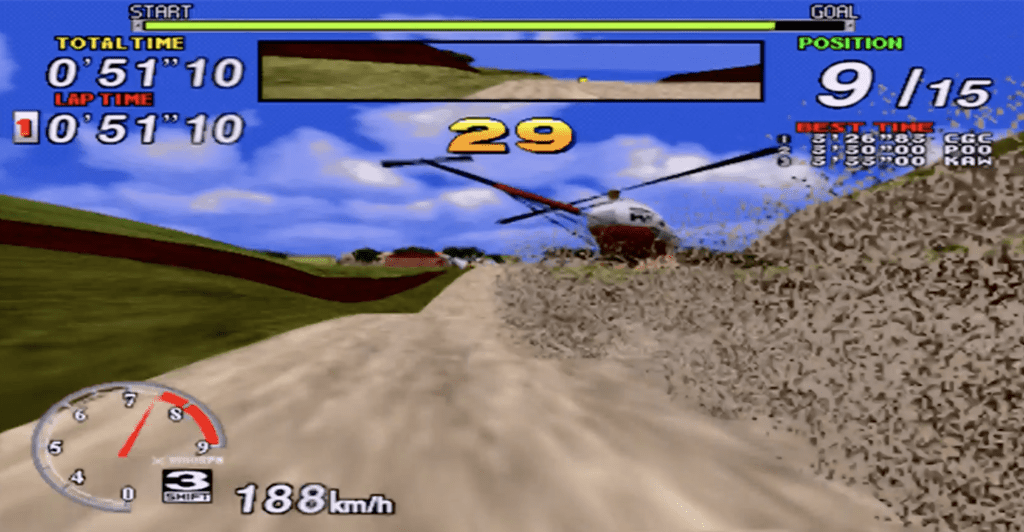

Then there were the insane eight-player link-up capabilities of the Virtua Racing arcade cabinet, complete with an extra TV replay-style camera view and even a 3D announcer, Virt McPolygon. Sega was in another league. And when Sega Rally came along with its jumps, zebra and helicopter, it really was “Game Over, yeah!” No other arcade game ever topped the brilliance of Daytona USA and Sega Rally Championship – including their own sequels.

But while Sega ruled the arcades for this time, that time itself couldn’t last forever, as home technology started to catch up.

Slowly at first, with that 16-bit attempt at Virtua Racing and then arguably the dodgiest launch game ever in the shape of Daytona USA on Saturn. But then the company started to hit its stride at home too. Sega Rally on Saturn brought that Model 2 coin-op into your home with faster motion, more to do and even a split-screen, two-player mode.

Then Dreamcast started to bring even the most cutting edge arcade games home without obvious compromise, thanks to the Naomi arcade board, which was basically a Dreamcast but with double the RAM. Interviews from the time spoke of continuously pouring two metaphorical cups into one to enable the home conversion of Crazy Taxi, but whatever the method, the result was incredible.

Then there’s Ferrari F355 Challenge, a coin-op that simulated the real car on real circuits including Suzuka, Long Beach and Monza. The difference in quality between the best home sim at the time – Gran Turismo 2 – and this arcade masterpiece was night and day. So pronounced, in fact, F355’s physics simulation still stands proud alongside today’s sim racing giants.

Of course, it had better-than-life weather, drenching the Long Beach tarmac with golden sunset light, but idealising and romanticising motor racing is what Sega did best. But in this instance, it simulated reality while adding magic to it.

And while the home conversion was spot-on (and included even more tracks), the arcade’s three-screen cabinet version began the trend for elaborate, sit-in sim racing setups. Even without this, the game was the most realistic driving experience you could get, and Dreamcast just kept pumping out Sega arcade conversions, including the best-at-the-time home version of Daytona USA.

But then people turned against arcades and even turned the word itself into a dirty word. Dreamcast died and since arcades were largely redundant, that was the end of Sega’s phenomenal golden age of racing games. Yu Suzuki left Sega and the mighty AM2 division faltered and fizzled out. There’s been a new arcade Daytona game recently but it’s not much good, truth be told.

And so gamers like myself are left seeking out scraps. Like a record collector who happens across a Beatles EP they never heard, sometimes there are still some gems to discover, and also like a record collector, I’m only interested in the originals – no emulation for me.

I’ve only ever played Scud Race (Daytona’s pseudo-sequel before the real Daytona 2) once, way after its release because it’s never received a home conversion, despite a very promising demo shown off on early Dreamcast units. I only sampled Power Drift when M2 converted it to 3DS – quite brilliantly, I might add.

So I’m down to just some three titles from this golden era that I’ve never played: the arcade version of Turbo OutRun, the arcade version of Super Monaco GP and… well, Rad Mobile – the one with the little Sonic dangling from the rearview mirror.

It’s slim pickings but I’m in no rush to play them. It’s the metaphorical last of the summer wine and when it’s gone, it’s gone. But my goodness, very few others taste anywhere near as sweet as a ’90s Sega racer.

Chat with the Community

Sign Up To CommentIt's completely Free