This year marks the 30th anniversary of Need for Speed. In that time, the franchise has experimented, taken surprising risks and reinvented itself to stay relevant, becoming one of the longest-running and best-selling racing game franchises with over 150 million sales.

During a roundtable event celebrating this milestone attended by Traxion, veteran developers look back at Need for Speed’s illustrious 30-year history and why the series has stood the test of time.

The series began in 1994 as a semi-serious driving simulator developed in collaboration with American automotive magazine Road and Track. The result was Road and Track Presents: The Need for Speed, initially released on the doomed 3DO home console before being ported to PC, PlayStation and Sega Saturn.

Arriving several years before Gran Turismo popularised driving simulations on consoles, The Need for Speed put players behind the wheel of exotic sports and supercars like the Ferrari 512R, Lamborghini Diablo and Toyota Supra MKIV, speeding down winding open roads while evading the cops.

This was a time when licensed cars were rarely seen in racing games. Developer EA Canada team was no stranger to driving games with licensed cars, however, having developed the first two Test Drive games as Distinctive Software.

“If you think about the first inception of what The Need for Speed was, it was really accessible,” Criterion Games Producer Patrick Honnoraty, who has worked on Need for Speed since 2012, reflects.

“I remember going to what was probably a local video game or computer shop at the time, and me and my friends saw it on the 3DO. We were like, ‘What’s this?’ We all jumped on it, on the 3DO, and you felt badass.”

“Being able to drive it, being chased by the cops – there wasn’t an experience like it at the time. I think that it’s tried to stay true to that formula. It’s still accessible today.

“A lot of car racing games are not so easily accessible, so people still have the option to jump in and have fun in a Need for Speed game.”

The thrill of the chase

The Need for Speed’s sequel, 1997’s Need for Speed II, doubled down on accessibility with a more approachable, arcadey handling model, which has remained a core part of the series’ DNA ever since.

Meanwhile, the third game, 1998’s Need for Speed III: Hot Pursuit, introduced another franchise staple, with pulse-pounding police chases creating a sense of risk and consequence – something that still sets the series apart today and is “a key contribution to the racing scene” according to Senior Creative Director John Stanley, who started working on Need for Speed in 2010 at Criterion.

“One of the key things with Need for Speed is it’s not afraid to take risks and do something different,” he says.

“It sits apart from other racing games in the genre…it’s still the only franchise that delivers on consequence – that thrill of the chase.”

“Nothing else in the genre does that – that sense of pressure and thrill you get running with your car, having a whole bunch of loot and the cops on your back and trying to get them off. It’s that one more: do I do one more event, one more piece?”

Police chases would also be a focal point in 1999’s Need for Speed: Road Challenge (known as High Stakes in the US) and 2002’s Need for Speed: Hot Pursuit 2.

However, the series would reach new heights in the 2000s with the two most popular entries its 30-year history: Underground and Most Wanted.

“We didn’t know what we had” with Need for Speed Underground

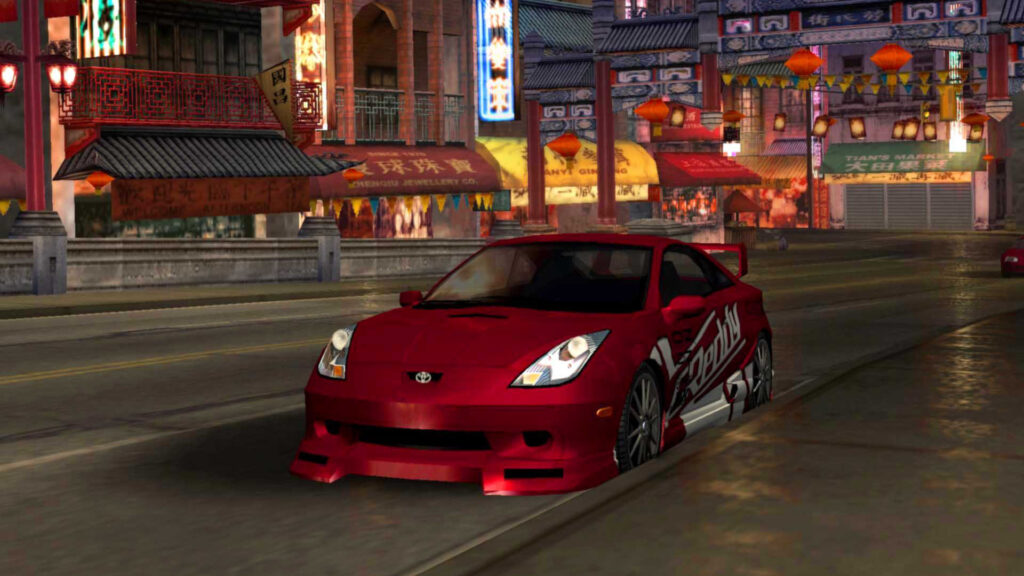

Released in 2003, Need for Speed: Underground took the series in a new direction, focusing on customisation inspired by the rise of tuner car culture. Looking back, Wiebe admits the studio didn’t expect Underground to become a fan favourite.

“It was so addictive to play,” Justin Wiebe, an EA veteran who now works on the Battlefield series at Ripple Effect Studios, recalls.

“It was the introduction of things like drag racing for the first time, where it was a completely new way of playing at high speed. We were starting to explore other new emerging racing genres like drift racing and starting to bring all of these new and cutting-edge ideas, and then mixing in with customisation.”

“We were pioneering at that time. We didn’t know what we had. But everybody there was bought into the vision of it and the vision was so clear for what we wanted to do. And Underground hit it.”

Introducing customisation was a turning point for the franchise, with Underground allowing you to modify your car with eye-catching bodykits featuring massive spoilers, flared wheel arches and underglow neon lights.

This remains a core part of Need for Speed, but creating these customisation parts is considerably more complex now.

“Advances in technology and rising player expectations enabled us to explore levels of fidelity and experiences that weren’t achievable 10 or 15 years ago. The cars in NFS are far more intricate now compared to the earliest days of the franchise.” Senior Vehicle Artist Frankie Yi explains.

“The biggest challenge is, hands down, dealing with the vast amount of content we produce for each car. Making sure they all meet the quality standards we’re aiming for. Say a car has three body kit designs. That’s three front bumpers, three rear bumpers, three side skirts, three front fenders, etc. That tallies up to 15, 20 individual parts.”

“Allowing the player to seamlessly and smoothly mix and match those parts sounds simple, but it involves a significant amount of work. You run into issues where that part doesn’t fit with that. There are different variations in bumper widths, fender shapes, fender sizes…the list goes on.”

“The panel lines, shut lines – nothing lines up. We have to build out every single part combination out there. You take that 15 to 20 individual parts, and you multiply it to an additional 60, or well over 100. It depends on the car. It’s a ton of work, but this allows the player to have thousands of car combinations. And who doesn’t want that?”

“So now you know why, in earlier Need for Speed titles, we just restricted the body kit to be equipped as one whole unit. But honestly, where’s the fun in that?”

For Honnoraty, customisation is integral to Need for Speed. “When customisation has not found its way into the priorities that we’ve set, and it’s been removed from the game, I think the game suffered,” he says.

Underground was a dramatic shift for the franchise, swapping exotic supercars with Japanese imports like those seen in The Fast and the Furious and hot hatchbacks.

Wiebe feels that keeping up with trends and embracing current car cultures is key to Need for Speed’s enduring appeal:

“You can go all the way back and look at car culture from the explosion of the muscle cars in the 70s,” he says.

“The rise of the exotic cars that lots of us as kids…Magnum, P.I. and all these amazing shows with these super amazing exotic cars. And we all just wanted to grow moustaches instantly and drive Ferraris, right?”

“Getting the thrill to experience the rise of the customisation era. The idea that you can grab your grandma’s station wagon and turn it into a 600-horsepower behemoth and throw a dragon on the side and say ‘this one’s mine good luck beating me’.”

“Eventually, that culture changed. Then it became the rise of the sleepers because everybody started cracking down on tuner racing. Then it was about who had the most secret car that wasn’t so showy, but don’t challenge me because I’ll blast you on the line.

“It’s that kind of culture that makes Need for Speed what Need for Speed is. It’s about tapping into the relevancy of car culture.”

A year later, Need for Speed Underground: 2 took the series open world for the first time. Instead of iterating on Underground, the next entry needed to do something different again.

“We kept asking ourselves, what do we do now? How do we one up this?” says Wiebe. The answer was Need for Speed: Most Wanted.

A risky move

With Executive Producer Michael Mann stepping in, Most Wanted was all about taking risks. Getting caught meant losing your car, increasing the tension when running from the cops.

“He [Mann] said, ‘I want to make it the most illicit experience we’ve done to date. I want to bring in the cops, and I want to make them feel so threatening like they are in the real world,’” says Wiebe.

“So that was the mandate to me: take these cops and make everyone absolutely terrified of them. And I said, ‘Then Mike, I’ve got to take away people’s cars that they earned. I’m going to impound them, and they’re going to lose them for a while.’ He was like, ‘do it!’”

“That’s the kind of stuff where we took risks. It’s a franchise that’s big but also unafraid to try to take risks, to do things differently, to challenge the norm. That’s what I love about working on the franchise.”

Wiebe even appears in Most Wanted as Taz, number 14 on the ‘Blacklist,’ a list of 15 street racers most wanted by the Rockport police force. Each racer’s crimes could also be viewed in a ‘Rap Sheet.’ “There weren’t that many games with those kinds of progression systems that came together – especially in a racing game,” Honnoraty notes.

According to Wiebe, Most Wanted nearly went in a different direction. “Somewhere in development, we started going in a different direction, and it didn’t match the initial vision we had,” he says.

“We all got in a room, and we said how did we get over here? Look how amazing that is. And we had a major course correction about halfway through, saying, ‘We’ve got to go in that direction and focus on the key ingredients like making it feel more illicit’.”

“Even the stats, like let’s hack the cop database to show you your own Most Wanted stats because that’s more cool and elicit feeling than just going to a menu and viewing your racing stats.

“It’s those kinds of little decisions that kept creating that narrative and fiction that made it what it is today.”

This course correction paid off. With nearly 18 million copies sold, Most Wanted became the best-selling game in the franchise by a huge margin. Nearly 20 years later, Most Wanted still resonates with Stanley.

“I cite Most Wanted so much within the studio. Just around the way it managed to weave together the narrative, gameplay and progression. Executing that in a game is so important. Most Wanted is a masterclass in that,” he says.

Most Wanted introduced players and car enthusiasts to the BMW M3 GTR E46, a race car that competed in the GT Class of the American Le Mans Series in the early 2000s. Since appearing in Most Wanted as a hero car adorned in a striking blue and silver livery, it’s now Need for Speed’s most recognised car.

“I think it’s safe to say that probably our most iconic car in the whole franchise is probably the one that was most unexpected at the time. Just dropping a full-blown race car into Most Wanted was unknown at that point. And look where it is now,” says Criterion Vehicle Art Director Bryn Alban.

“20 years later, it’s still our most iconic car. We still celebrate it massively internally within the development team, but our players love that car as well. I think that one epitomises what Need for Speed can bring to the table in terms of making iconic cars out of things that wouldn’t be expected in the first place.”

To celebrate its legacy, BMW recently converted a real M3 GTR into a Most Wanted hero car replica, displayed at the BMW Welt Museum in Munich until 6th January 2025.

Stanley adds that the “context we lay on the car” makes the M3 GTR’s appearance in Most Wanted more memorable and special. “In Most Wanted, there’s a whole story about the M3 and what happens to it,” he says.

At the start, your M3 GTR is stolen by Razor, the most wanted Blacklist street racer, before being reunited with your cherished car after beating him at the end of the game.

Going off track

Taking risks hasn’t always paid off. The late 2000s and early 2010s were an experimental time for Need for Speed. Contrasting Most Wanted’s illegal street racing, 2007’s Need for Speed: Pro Street bewildered some fans with its sanctioned racing and professional sporting events.

“People are like, ‘what about the story, what about the cops?’ Yes, we understand those aren’t there, but we made the decision that we want to go big. We want to bring car culture to sanctioned racing tracks and that was the vision for this year’s NFS,” Wiebe asserts.

Meanwhile, 2010’s Need for Speed: The Run centred on a cross-country race with cinematic action setpieces that would make Michael Bay blush and, controversially, quick-time on-foot sections.

“We really tried to break some new ground there. We talked about getting out of the car. We had all these grandiose visions: it’s going to be more than just racing. Characters are going to get out of the car. But then we realised very quickly that we couldn’t really do that, so we introduced some quick-time events. We all love quick-time events, right?” Wiebe jokes.

The Run was envisioned as “a grand racing adventure,” with you playing as a street racer named Jack racing from San Francisco to New York to pay off a mafia debt.

“We wanted it to feel like your life is on the line, that it’s more humanised than ever before about the character and the story that they’re doing, racing from coast to coast,” Wiebe explains.

“I’ll be the first to stand up and say that didn’t really work,” he admits. “But I’m proud of the fact that we tried it.”

“I was on a fan forum a few months ago and was shocked at how highly rated some of the fans made that game. I thought, ‘That’s a bit of a lump of coal in my resume.’ But it turns out that it has a massive cult following. There are certain people who absolutely adore that game.

“That brought a little joy to my heart that we took a risk and there are some people that found something to love about it.”

ProStreet and The Run received mixed reviews, but Wiebe feels it’s important to stick to your vision. “If you try to make something for everyone, what you wind up doing is watering it down and making something for nobody in particular,” he says.

“And so, you really do have to be ruthless with your vision and say, ‘We’re going to take this part of what people love about Need for Speed, and we’re going to bring it to the next level.’ And then what does that mean?”

“And then we’re looking, and we’re like, ‘We know people are going to miss X, Y and Z because that’s what Need for Speed is to them – are we ok with that? How do we massage it? How do we manage the message for what this particular Need for Speed is going to be about?”

“That’s the hardest thing is to make these decisions that we know are going to be polarising for players, but that we believe is best for that particular product in that moment in time.”

“It’s almost impossible to get it 100 per cent right all the time”

With the franchise steering in different directions over the years, keeping Need for Speed fans happy is one of the toughest challenges for Honnoraty. “The biggest challenge we face is the age of the franchise. It’s been so many different things and appeals to so many people,” he says.

When showcasing Need for Speed Payback’s action-packed highway heist mission at EA Play, Honnoraty noticed that players would constantly compare it to Underground or Most Wanted – even though they are “completely different.”

“People carry with them the feeling they had when they played those games,” he says.

“Some of them skipped ones and came back from others. I think that’s the hardest thing today. It’s reconciling what Need for Speed means to players. When we go in one direction on something, it doesn’t quite work. It doesn’t appeal to certain players, or we go in another direction.”

“It means so much to so many people. Everybody’s got a different opinion of what a good Need for Speed is,” Alban adds.

“Trying to appease everyone at all times is super difficult. Even down to the nitty gritty details of what customisation we put on our cars. It’s such a divisive subject to our players that it’s almost impossible to get it 100 per cent right all the time.”

“So, when we do get things somewhat correct, it’s great. But when you see those comments where you’ve missed something, it really hurts. It’s tricky and tough to get that balance of making the perfect Need for Speed.”

For Stanley, three aspects have remained constant in Need for Speed, which he dubs the “three Cs”: context, customisation and consequence.

“Over the 30 years of Need for Speed, various titles have indexed on these in different ways. By and large, the franchise really hits on these,” he explains.”

“What we mean by context is some people might call this story or narrative. But for Need for Speed, it’s more than that.

“It’s about giving context as to why the players are doing things. Why am I taking this car from point A to B? Why are you asking me to upgrade this car from a tier B to a tier A? It’s the context that comes behind it.”

“And the additional thing we learned over the last couple of years is about authenticity within car culture too. The more we can wrap our context and what we’re doing around that, the more it resonates with our players.

“There are lots of ways you can push the direction of the narrative and gameplay as long as you give the context behind it.”

“On the customisation side, that’s been a key staple for Need for Speed for a long time. We’ve been a forerunner there and setting innovation. I don’t think there are any cars out there within the racing game scene that you can take as far as we can in Need for Speed.”

“Self-expression is something that’s really important. You can change the silhouette of the car, the wrap, the stance and the way the car sounds. That’s something for us going forward that we want to take even further.”

Finally, consequence is about risk and reward. “You can boil this down to the cops in the game, but it is more than that,” he continues.

“That sense of tension: do I just go out and do one more race and risk all the loot I’ve accrued? It’s something that really sets us apart.”

“It’s been lots of different forms across the years, be it our heat system, side bet system, canyon runs – there’s so much stuff that we’ve done in the past. And it’s definitely a piece I’d like to index more in the future.”

“Need for Speed is always too ahead of its time”

However, while not every game has been well received by fans, Honnoraty believes that trying new ideas has made the series feel fresh, exciting and unpredictable over the last 30 years.

“Need for Speed has never remained the same. From one iteration to the next, it’s always had something that was different,” he says.

“You look at Underground and Underground-specific racing and events that it had. You look at then how it moved to an open world. You look at almost the complete change there. The conviction to go after the illicit nature of it and then ProStreet; completely different direction and focus. Those things have still continued.”

Before Criterion, which developed the 2010 Hot Pursuit and 2012 Most Wanted reboots, returned to the series with the most recent entry, Need for Speed Unbound, Honnoraty worked on several Need for Speed games at EA Ghost Games, introducing new ideas while staying faithful to the series’ history.

“We did a kind of version of Hot Pursuit with Rivals. We then changed and went back to a reimagination of what Underground would look like today and brought back customisation,” he says.

“We then focused on an even more action-orientated game [Payback] and moulded some of those things together to create something like Heat. We brought in Heat’s idea of risk and reward and doubled down on it for Unbound to create the calendar system.”

“So it’s always reinventing, always trying to pick the ideas that make what you do with these vehicles interesting; something that’s slightly beyond the racing. But the racing is always still at the core of what they are. That’s what we’ve done for good and for bad.”

“Those things, as risks as they are, don’t always work. They don’t always resonate with players. But you guarantee we’ll always do something different.”

“Every Need for Speed I’ve worked on, when it’s come out, it’s been ‘oh my god it was no good. It was rubbish.’ People didn’t like it. And then years pass, and it’s like, ‘Ah, it was so good, it had these great elements to it. It was the best NFS, why don’t you go and make one back like that?’”

“Need for Speed is always too ahead of its time. Every time we bring one out, it doesn’t strike, but people look back on them so fondly.”

What are your favourite Need for Speed memories over the last 30 years? Let us know in the comments below.

Chat with the Community

Sign Up To CommentIt's completely Free

NFS has been dead to me since NFS 5 Porsche Unleashed.