Thanks to the big-budget Hollywood movie Gran Turismo: Based on a True Story, focus has naturally fallen on the original ‘Gamer to Racer’ GT Academy competition and how it produced a succession of racing drivers; including the film’s subject, Jann Mardenborough (played by Archie Madekwe).

So, ahead of its European release on the 9th of August, we felt now was a great time to delve into the history of the GT Academy and take a broad look at its successes and failures, and why it was an important step towards sim racing being accepted by the wider motorsport community.

What was the ‘GT Academy’?

GT Academy was a competition masterminded by Nissan’s Darren Cox, who formulated a plan to turn gamers into real racing drivers. After establishing a partnership with Sony’s Gran Turismo gaming platform (developed by Polyphony Digital), Cox helped coordinate Nissan’s role in the competition, with the Japanese manufacturer’s road and race cars featuring prominently.

Originally devised as a one-off European event in 2008, the success of the GT Academy format prompted Nissan and Sony to try again in 2010, this time adding a USA-based series. Further Nissan GT Academy operations were established in the Middle East/Africa, International and Asia regions, with separate national series in Germany and Russia.

The GT Academy was conceived with television in mind, with the first series charting the progress of participants who’d qualified via Gran Turismo 5’s in-game GT Academy mode and subsequent LAN competitions.

The gamers were filmed going through various challenges, supposedly designed to help develop important race car-driving skills. These tested both the contestants’ physical and mental acumen but veered more towards reality TV-style entertainment than serious motorsport preparation at times.

Why on earth would drivers need to physically haul their cars down a track, for example, or take part in a Ninja Warrior style gameshow. And how about some monster truck driving? Huh?)

New beginnings

For the first GT Academy in 2008, 12 European countries held national finals where each nation’s fastest 20 drivers duked it out to become one of the fastest 22 Europeans to be selected for the week-long GT Academy Boot Camp at Silverstone.

Fitness tests, media training and psychology workshops were dovetailed with more familiar circuit-based driver training, with contestants sampling karts, Caterhams and Nissan 350Zs, mentored by the likes of Formula 1-winner Johnny Herbert and GT racer Rob Barff.

In a slightly mawkish way, the 22 racing hopefuls were whittled down to eight over the week – it was a reality show, after all – with underperforming contestants asked to leave every day.

A one-day final shoot-out determined two winners, with Lucas Ordoňez and Lars Schlömer selected as the first-ever GT Academy champions.

Rookie racers

Their prize was a drive in a GT Academy-backed Nissan 350Z GT4 in the Dubai 24 Hours – but first they had to prove they had the skills to drive competitively and safely. Sadly, Schlömer missed the cut – deemed underprepared for professional racing – leaving Ordoňez to fly the flag for the ‘Gamer to Racer’ competition.

He performed well enough to be kept on by Nissan as a professional race driver – despite the car facing numerous mechanical issues – later finishing runner-up in the 2009 GT4 European Cup with Nissan-affiliated RJN Motorsport.

The way Ordoňez had taken to real racing prompted plans for more GT Academy competitions, while the Spaniard went on to secure two class podiums at the 24 Hours of Le Mans between 2011 and 2015 – perhaps the greatest test of a sportscar driver’s abilities. Not bad for a gamer…

In the 2010 edition of GT Academy, Frenchman Jordan Tresson was victorious and, in the following year, it was Jann Mardenborough’s turn to take European honours, with Bryan Heitkotter claiming the USA crown.

In total, there were 22 Nissan GT Academy winners thrust into the world of motorsport (or nearly, in the case of the unfortunate Schlömer). The question is, after Nissan’s advanced coaching how many of the GT Academy alumni forged successful careers?

Jann Mardenborough

Undoubtedly the biggest success story of GT Academy is Mardenborough. The young Brit took part in a round of the European GT4 Cup in 2011 before embarking on a Blancpain Endurance Series campaign in a Nissan GT-R GT3.

He competed alongside Alex Buncombe in the British GT Championship in 2012, taking a single win (notably, it was the closest winning margin in the championship’s history, with Mardenborough holding off a charging Jonny Adam at the line), finishing sixth in the championship, before a hectic 2013 saw him travel the world competing in single-seaters and GTs.

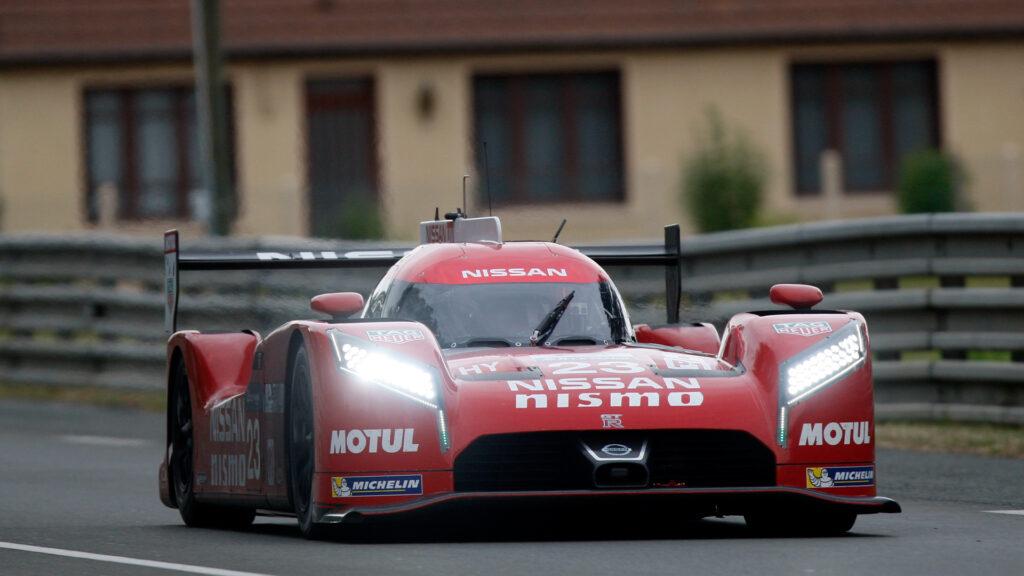

2013 also saw his Le Mans debut, achieving an LMP2 podium (sharing with Michael Krumm and Ordoňez), with a step up to the Formula 1-supporting GP3 series in 2014, which resulted in two starts in GP2 in 2015. The same year would see him drive the ill-fated LMP1 Nissan GT-R LM Nismo on his return to Le Mans…

Cost cap

His father, footballer Steve Mardenborough, took his son karting at the age of eight and it was clear Mardenborough had a natural talent for motorsport. However, travel costs proved problematic:

“I stopped when I was 11,” said Mardenborough in an interview with The Guardian, “because it got too expensive.” Gran Turismo 5 was the next best thing for the young motorsport enthusiast, which led to him beating some 90,000 other gamers for a place in the GT Academy.

Mardenborough used his innate speed and skills picked up from Gran Turismo – like racing lines, threshold braking and racecraft – and put them into practice. And he wasn’t fazed:

“It felt completely normal. I’d never power-steered a car before, had only ever done it in a game. I was controlling it just with the throttle and it was completely natural to me,” Mardenborough commented.

Le Mans debacle

Nissan’s 2015 LMP1 Le Mans operation was masterminded by Cox, who was made Global Head of Brand, Marketing and Sales at NISMO (Nissan’s motorsport division) after the initial success of GT Academy.

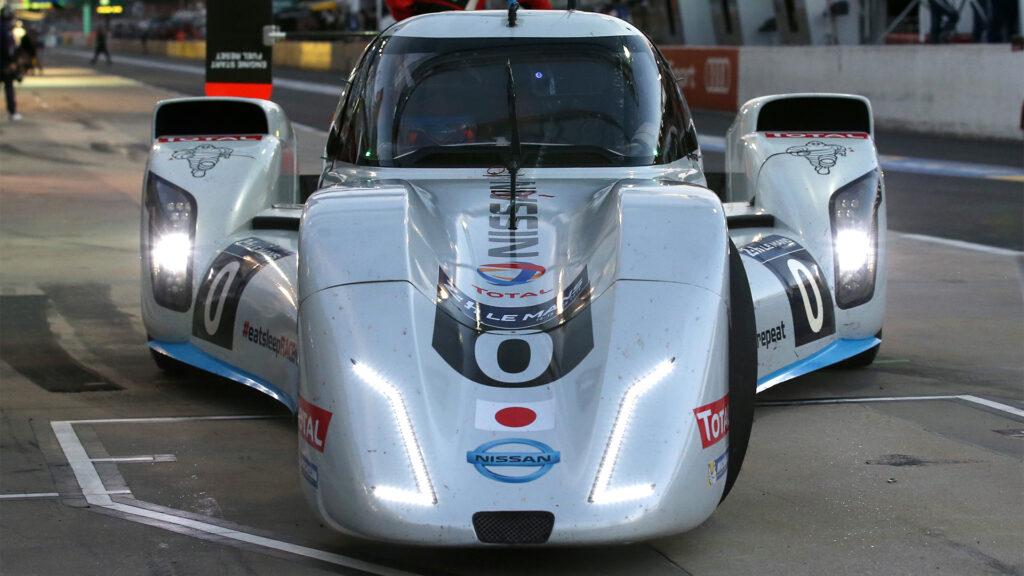

Cox was responsible for overseeing Nissan’s motorsport operations around the globe, spearheading a first stab at Le Mans in 2014 with the Nissan ZEOD RC Garage 56 entry for innovative vehicles. This preceded a full-on assault for overall victory a year later.

This became a turning point in the Nissan and GT Academy relationship. The car designed by Nissan was unorthodox: it was front-engined and most of its power arrived through the front wheels. But its frontal aerodynamics were thought to be efficient enough to create less drag – crucial around the Circuit de la Sarthe’s long straights.

However, the car was woefully off the pace and qualified at the back of the LMP1 grid, some 20s off the pole-sitting Porsche 919 Hybrid of Neel Jani.

Mardenborough shared the #23 car with experienced professionals Olivier Pla and Max Chilton, with the car expiring with just an hour to go. Ordoňez was in the #21 car with Tsugio Matsuda and 2012 Russian GT Academy winner Mark Shulzhitskiy, but they lost a wheel before the halfway mark and retired.

Let down

The team’s only all-professional lineup, consisting of Alex Buncombe, Harry Tincknell and Michael Krumm in the #22 car, finished the race but wasn’t classified thanks to failing to complete the required race distance. The #22 car’s best race lap was some 18 seconds off the fastest (and only marginally ahead of the top LMP2 car, ironically powered by a Nissan engine).

The GT Academy alumni had performed admirably compared to their professional team-mates but were badly let down by an ill-conceived car. It was an embarrassing episode for Nissan, with Cox leaving the company in October 2015. Soon after, Nissan pulled the plug on GT Academy.

Orlando Bloom’s character in the Gran Turismo movie – Danny Moore – is loosely based on Cox, who after leaving Nissan in 2015 went on to establish another GT Academy-style ‘virtual racer to real racer’ competition called ‘World’s Fastest Gamer’, helping introduce winners James Baldwin and Rudy van Buren to the world of motorsport.

The other side

As Lars Schlömer can attest, not every GT Academy graduate has fond memories of the scheme. Jordan Tresson endured a tough debut season in the 2012 FIA World Endurance Championship (WEC) after his GT Academy win in 2010 and was duly dumped by Nissan at its conclusion:

“It was not nicely at all [how it ended]. I knew I had nothing [for 2013] in March through a press release – no one told me anything before and by the time it is March it’s too late to still find something. To do it with a press release and no one having the balls to call you to explain the situation – it wasn’t nice at all,” the Frenchman stated in an interview with GT Report.

Thankfully, Tresson was comforted by an offer to drive in the Nordschleife-based VLN series for Ring Racing – thanks to the patronage of Gran Turismo chief Kazunori Yamauchi – going on to pick up regular GT3 drives in subsequent years.

Some of the GT Academy champions disappeared as quickly as they burst onto the motorsport scene, while others pursued other interests. For 2012 European winner Wolfgang Reip, however, he had to end his motorsport career prematurely thanks to a severe case of hyperacusis, a hearing condition where noise causes him physical pain.

Besides crippling tinnitus, Reip’s hyperacusis was caused by repeated exposure to loud noise from a motorsport career in which he conquered the Bathurst 12 Hours with 2013 GT Academy Germany winner Florian Strauss and Katsumasa Chiyo and became 2015 Blancpain Endurance Series (BES) champion.

Reip also went on to become a factory Bentley driver after GT Academy folded, proving he had the skills to continue racing outside the confines of the program.

Where are they now?

Lucas Ordoňez enjoyed a modestly successful career in professional motorsport, winning the Pro-Am Cup in the 2013 Blancpain Endurance Series before racing in Japan. But Le Mans in 2015 effectively ended his frontline driving career – barring occasional sportscar outings.

Today, the Spaniard maintains his role as a brand ambassador for all things Gran Turismo, offering commentary for the Gran Turismo World Series.

Mardenborough, on the other hand, has forged a professional racing career since the Le Mans debacle, moving to Japan to compete in Super Formula and the GT500 class of Super GT, with occasional outings in a GT3 Nissan GT-R (this time sponsored directly by the Gran Turismo franchise). He was also a Formula E test and sim driver for the Nissan e.dams team.

Despite a terrifying airborne crash at the Nürburgring Nordschleife in 2015, which claimed a spectator’s life, Mardenborough has implemented skills learned from Gran Turismo and the GT Academy into several seasons as a professional racing driver.

He too joined the list of GT Academy casualties at the end of 2020, however, when Nissan fired him after a poor Super GT season. However, this year Mardenborough resumed his career with an outing in the Fuji 24 Hours alongside working on the production of the Gran Turismo: Based on a True Story movie as a stunt driver and adviser. His goal is still to return to professional motorsport.

You can watch his remarkable ‘Gamer to Racer’ story on the big screen but the credits haven’t rolled on his motorsport career just yet.

Featured image: Nissan GT-R GT3, British GT Championship, Snetterton 2012. Alex Buncombe/Jann Mardenborough, Photographer: Ross McGregor

Chat with the Community

Sign Up To CommentIt's completely Free